Introduction

The “British Video Game Factory” is our effort to respond to the understanding of “British Video Games” as covered by the course. The mechanics underlying the gameplay are inspired by Lori Morimoto’s discussion of the “transnational” nature of contemporary media fandom and Ehrenreich et.al.’s interrogation of “Beatlemania,” along with Nick Webber’s discussions around the “Britishness” of British video games, alongside Iwabuchi’s discussion of conscious exports of Japanese products, wherein focus is given to the decision-making and regulatory processes at work in production, marketing, and export of specifically national flavours of intellectual property.

Gameplay

The player takes on a kind of a meta-role as a controller of the processes around the sale and localisation of creative products for foreign markets. Starting with a fixed budget of £100 million, the player must balance export and distribution costs against revenue from international markets, given imperfect, limited information and the potential for tastes and preferences to shift over time.

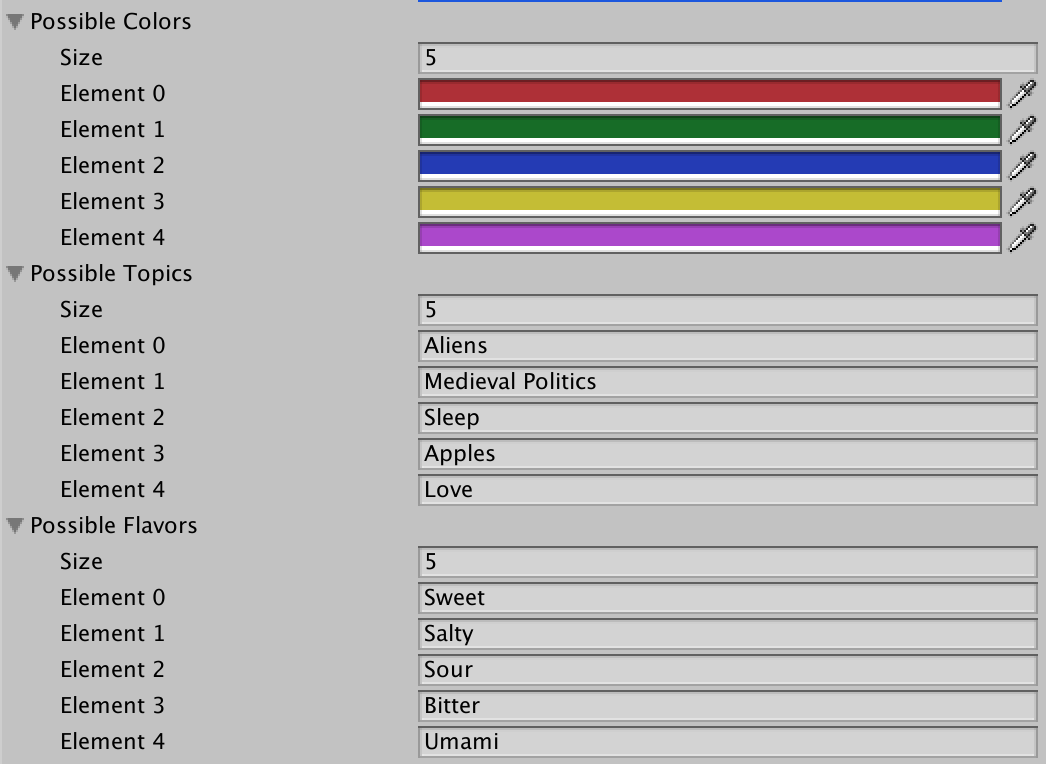

The “Creative Industry” in the game works as an independent entity: the player character has no influence over the products that the “Creative Industry” produces, nor do they have exact control over when the products are produced. The products produced are randomly generated from a pool of characteristics: Color, Topic, and Flavor. These characteristics represent abstractions of the notion of specific tastes of both local creators and international markets, and also attempts to encode the notion of ‘cultural odor’ (Iwabuchi 57):

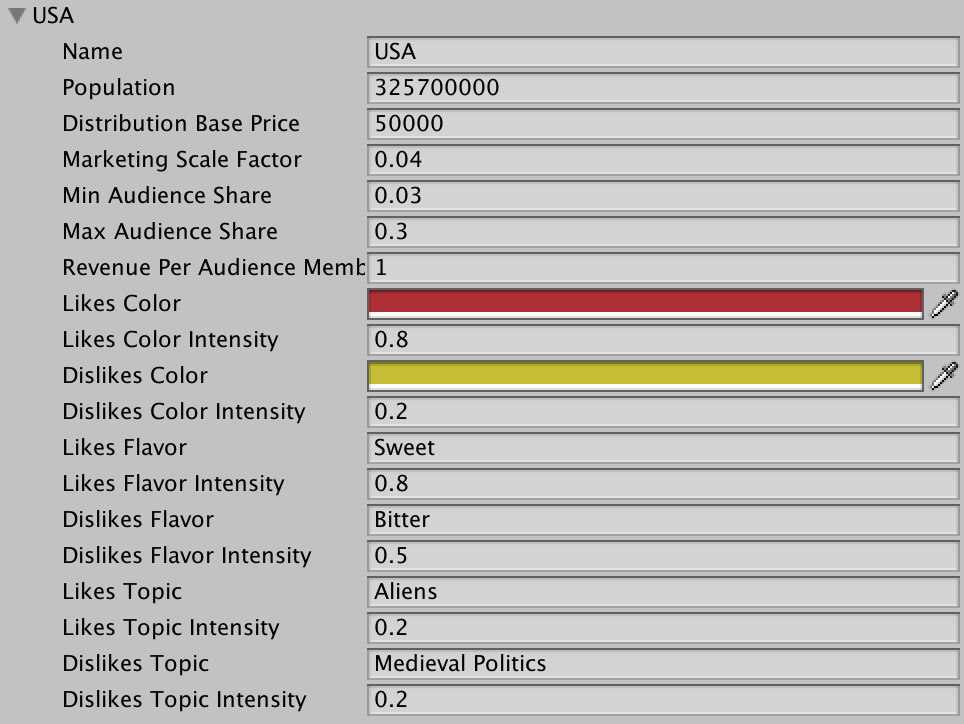

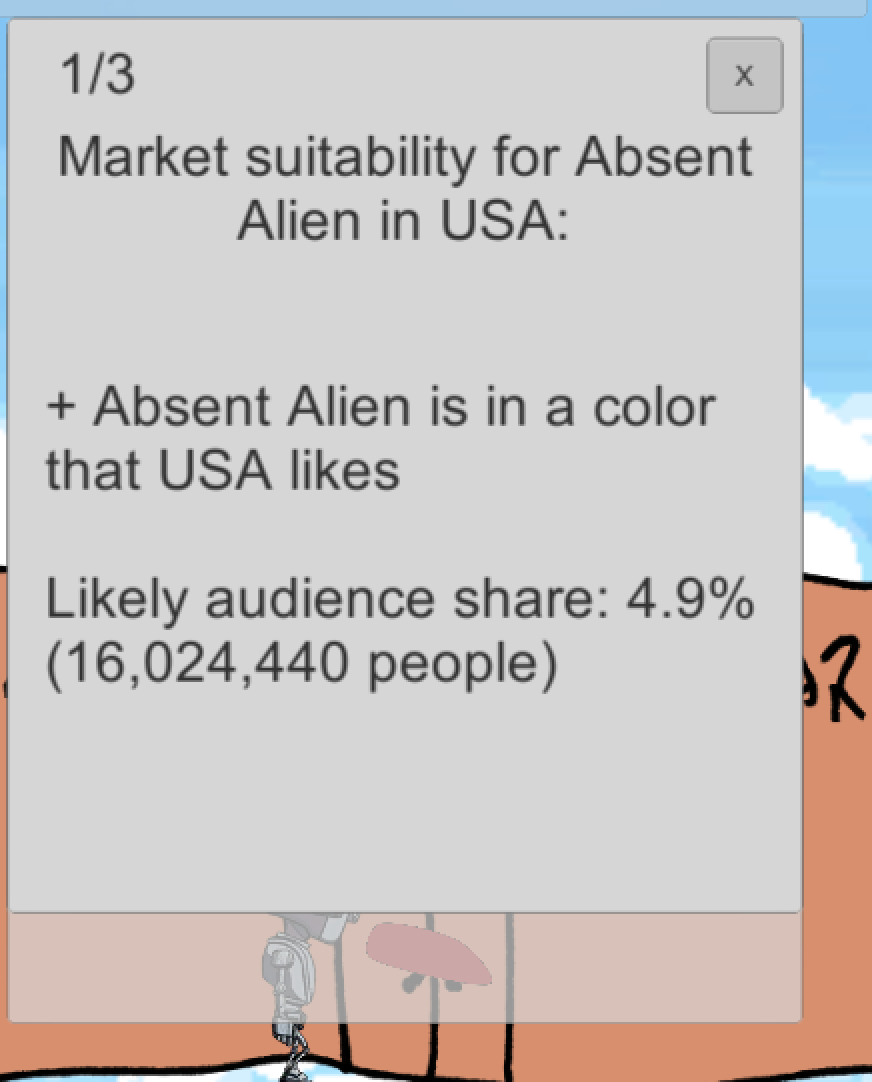

Each product produced by the “Creative Industry” lands on the ground in the game. The player character picks a product up and takes it first to “Market Research” where an audience share estimate is generated for each target international market based on the match (or mismatch) between the Color, Topic, and Flavor preferences of the the area or zone:

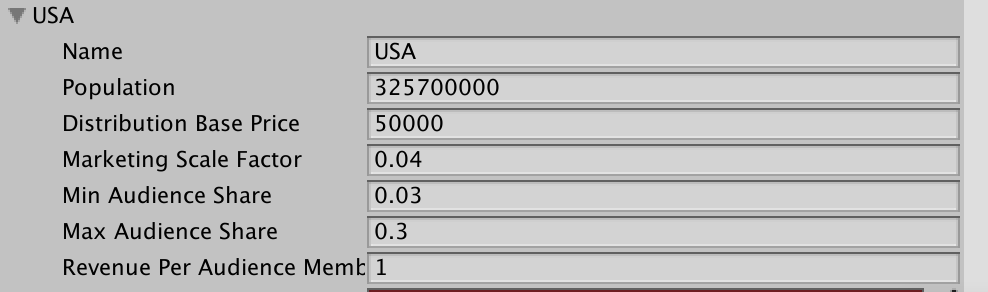

For example, if the product was red, this matches the “Likes Color” for the USA market, and so the likely audience share would be increased in proportion to the “Likes Color Intensity”. Conversely, if the product was yellow, this matches the “Dislikes Color” for the USA market, and so the likely audience share would be decreased in proportion to the “Dislikes Color Intensity”. The smart move, therefore, for maximising the market share to the USA would be to make sweet, red products that are about aliens. A product that was yellow, bitter, and about medieval politics would fail to sell very well at all.

This information, however, is not directly available to the user, unless, for example, the user presents a red product to “Market Research”, in which case the user would be told that USA likes red (although note that they are not told how much the USA likes red):

This reflects the general uncertainty around localising products for international markets, where “specific cultural contexts” inflect foreign fans’ “interpretation of foreign media” (Morimoto 281), and where neither the precise level of attention a cultural product will recieve, for example the “quirky and hard to explain” reaction to the Beatles touring the USA in the 1960s that is commonly known as Beatlemania (Ehrenreich 85).

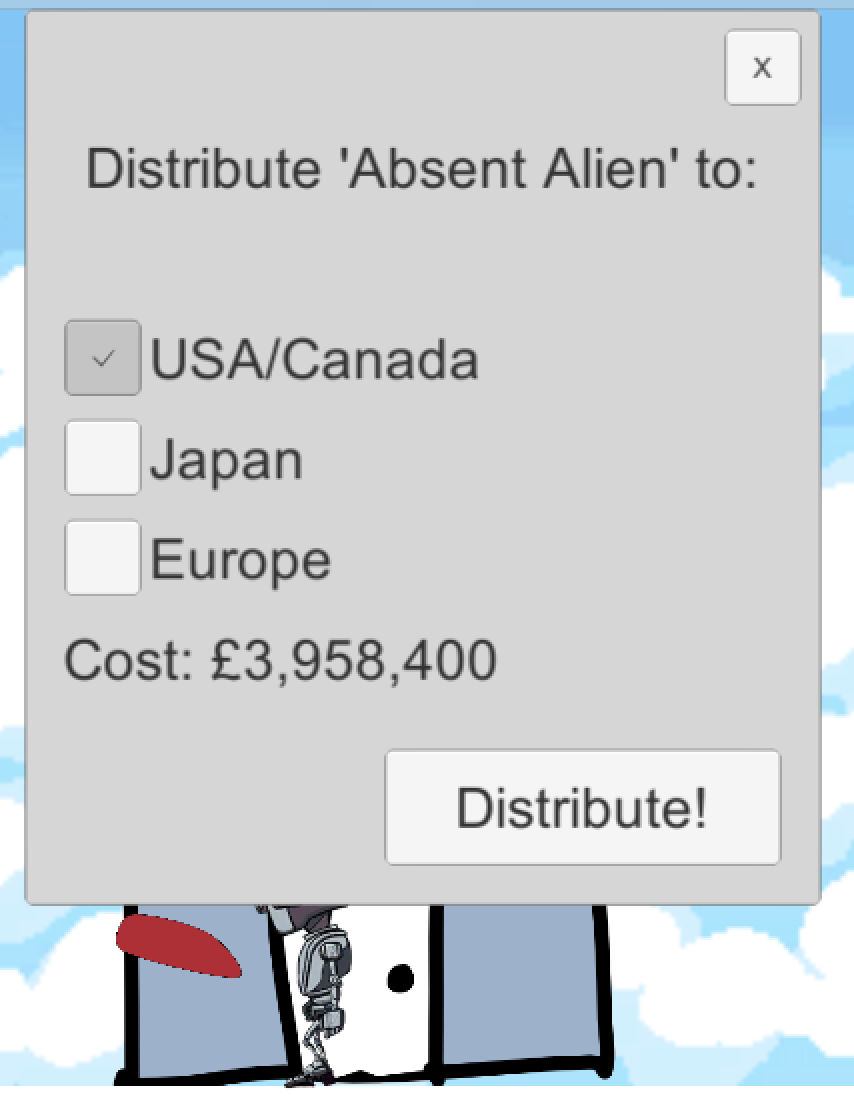

Next, the player carries the product the “Distribution”, where they choose target markets to distribute the product to:

Each market has a price that is calculated using information that is distinct to each market but hidden from the user, reflecting the differing costs of advertising and licensing in different regions:

The player can use the audience share estimates provided by “Market Research” to decide where to distribute the product, considering that some markets are more expensive the distribute to, and that it therefore perhaps does not make sense to distribute products to markets where they will not perform very well.

Upon distribution, the distribution costs are immediately withdrawn from the player’s remaining funds. Feedback about the relative success or failure of a distributed product is not immediately available – rather, the player will be informed after some time has passed about returned income from a particular product.

Discussion

The game mechanics in their current state have a number of issues, however the core loop feels satisfying and it seems clear that there is potential here. At the moment it prevents very little challenge, as it’s nearly impossible to run out of money. A traditional game design approach would suggest that it needs more “balance” in order to provide more of a challenge (Egenfeldt-Nielsen et.al. 103). However, a couple of alternative perspectives suggest different approaches. First, the experience is somewhat meditative, providing an alternative to the idea that games must be a “challenge” (Code, no page numbers). Second, in placing the player into position as a government official responsible for the export of British intellectual property to the world, the game can be seen as reflecting Britain’s position as a cultural superpower relative to nations in the world. To more effectively reflect this position, the target markets where cultural products can be exported to in the game itself should not be the current selection of relatively powerful regions such as Japan, the USA, and Europe, but rather smaller nations, perhaps former British colonies.

Planned but not implemented was a mechanism by which the various nations’ tastes and preferences would shift over time. If too many red products were exported to America, America might start to lose its preference for red. Conversely, a constant stream of green products might find a small but stable fan base, which could at some point cause a radical shift in the colour preference of American audiences in general.

Works Cited

Code, Brie. “Video Games are Boring”. Gamesindustry.biz (website), 7 November 2016. https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2016-11-07-video-games-are-boring (retrieved 30 July 2019).

Ehrenreich, Barbara, Elizabeth Hess, and Gloria Jacobs.“Beatlemania: Girls Just Want to Have Fun.” In Lewis, Lisa A. (ed) The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media. London & New York: Routledge, 1992.

Egenfeldt-Nielsen, Simon, Jonas Heide Smith, and Susana Pajares Tosca. Understanding Video Games: The Essential Introduction. London & New York: Routledge, 2008.

Iwabuchi, Koichi. “How “Japanese” is Pokémon?”. In Tobin, Joseph (eds) Pikachu’s Global Adventure: The Rise and Fall of Pokémon. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004.

Morimoto, Lori. “Transnational Media Fan Studies”. In Click, Melissa A., and Suzanne Scott (eds) The Routledge Companion to Media Fandom. London & New York: Routledge, 2018.

Webber, Nick. “The Britishness of ‘British Video Games’”. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 7 March 2018, pp 1-15.